Understanding youth labour markets in Australia

On Thursday we’re likely to see evidence that the “hot as hell” post-pandemic labour market is cooling. My colleagues and I have been following this closely - encouraged by the positive effects on workers associated with significant job opportunities, but mindful that we need to understand the risks of a future slowdown.

You will have seen posts related to this in terms of spending by displaced workers and income scars - and we will discuss this a lot more in the future. However, it is also important to look at specific groups who appear most vulnerable - today I want to focus on some insights pre-doctoral researchers at e61 have pulled together on the youth labour market.

Background jazz

Before kicking off I want to tell you a story from my life as a young macroeconomist. I would talk about unemployment in the media occassionally, which led to people calling me to tell me that i) I’m an idiot or worse ii) that there were specific areas where unemployment was more significant or more painful.

Now these callers were (mostly) right on both ;)

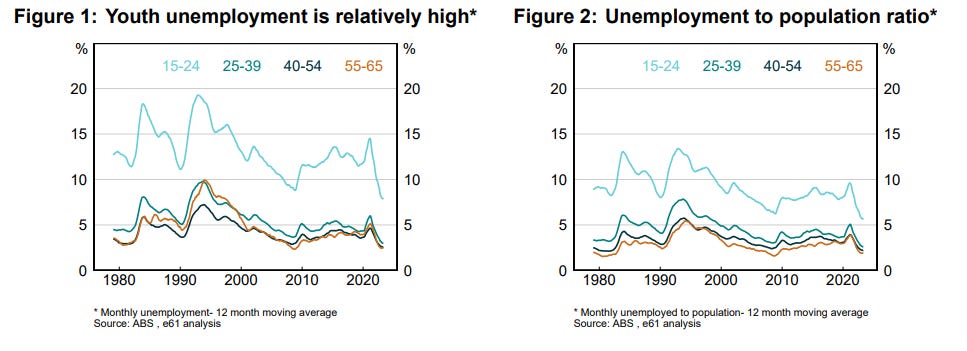

Looking at numbers alone it is clear youth unemployment is A LOT higher than unemployment for older age groups. Given that these are young people who want to work to also build skills - such unemployment seems very costly.

However, I was once on a panel on income inequality in New Zealand when I noted youth unemployment and its potential costs - just to be called out by a much higher profile economist for, again, being an idiot. Specifically he roughly stated that “clearly young economists nowdays have limited knowledge about economic statistics, history, or why they matter”.

He firmly noted that youth unemployment looks high because a lot of young people are in education - building those skills. If we added that group in youth unemployment wouldn’t look too bad.

Again fair points.

In such a complicated environment for understanding concerns about youth labour markets, it appears we genuinely need to pull together what data we have - and base these stories on hard and fast figures.

That is where the separate work of two amazing pre-docs - Jo Auer and Zach Hayward - comes in useful.

Painting a picture of youth unemployment

Lets start by thinking about youth unemployment with Zach. Contrary to the comments of the nameless estemmed economist above, the number of young people who are unemployed are indeed a high proportion of the population group.

However, interpreting this stock of unemployment relies on understanding the underlying flows.

Is youth unemployment high because a lot of young people transition into unemployment (either from school or by separating from jobs) or because it is danged hard to get employed again (a low job-finding rate). When young people leave are they doing so on the hunt for better work and conditions (voluntary unemployment) or because employers are simply more likely to fire young people (involuntary unemployment).

These details matter when judging whether “big number = bad” - in the extreme if all this unemployment measured was young people telling bad employers to shove off, and then quickly finding work, then this may actually be a good thing!

So what does Zach find? He finds that young people appear to find jobs just as quickly as other age groups, but are much more likely to leave - for both voluntary and involuntary reasons.

Following the approach of Zheng etal (2022), he find these separations are actually a bit lower than in New Zealand. And then also discovers the following:

This is cool - so I want to walk through it a bit. On the left we have overall separations - even after accounting for a bunch of differences between the groups, including their “tenure” at their job, young people are more likely to leave. But they are actually slightly less likely to be fired (the right graph) relative to prime age 40-54 year olds.

Now tenure is doing some heavy lifting here - young people will have lower tenure after all, and firms love FIFO (first in first out). But it doesn’t look like firms are targeting young workers alone - and a big driver of higher youth separations is the fact they i) voluntarily want to leave ii) by virtue of their age they have less experience/tenure which is a factor that makes everyone vulnerable.

Describing vulnerability - who is NEET

But there is a reason why we tend to emotionally gravitate towards concerns about youth unemployment rather than prime aged unemployment - a life shock early in a career can negative implications over the entire lifetime, and so in a lifetime basis can have large costs. Andrews etal (2020) shows this starkly for early career grads in Australia.

NEET is a wider category than unemployment, as it captures those who may be out of the labour market due to discouragement, homemaking responsibilities, and disability. As a result, trends in NEET can provide a richer understanding of changes in disadvantage than unemployment alone would.

Over the same long period Zach analysed, Jo found a reduction in NEET rates for young people. However, this hid some concerning stories below the hood when estimating the risk factors associated with NEET status:

Male NEET rates increased from the end of the mining boom - and directly following COVID were at levels comparable to the Australian depression of the early 1990s.

Regionally, NEET rates are very high - with much stronger youth labour market engagement in urban regions.

NEET is heavily concentrated among Indigenous Australians.

Falling into NEET when young is a strong predictor of experiencing NEET in the future - in other words, such experience is persistent.

The growing not in the labour force (NILF) status of young, regional, men was a concern Jo picked up on - and was shared in the lived experience of people she talked to during the project.

Putting this in context along with Zach’s work what can we say?

I think the message is - although it may be the case that youth unemployment on average is not as problematic as we may think, that doesn’t rule out that there are pockets of disadvantage where weak labour market opportunities create harm.