Previously we’ve talked about the cost of job loss in terms of revealed consumption responses - i.e. how do individuals cut their spending following job loss. This is a useful concept, and there is going to be more to say on this in the next year.

But a more basic point people may ask with respect to the cost of job loss - how much lower is someone’s lifetime income if they end up getting shoved out of their job!

Let’s chat about that while investigating some initial work my colleagues and I have undertaken at e61. For those who know things already, or don’t want to read a wall of text, here is the picture you are after:

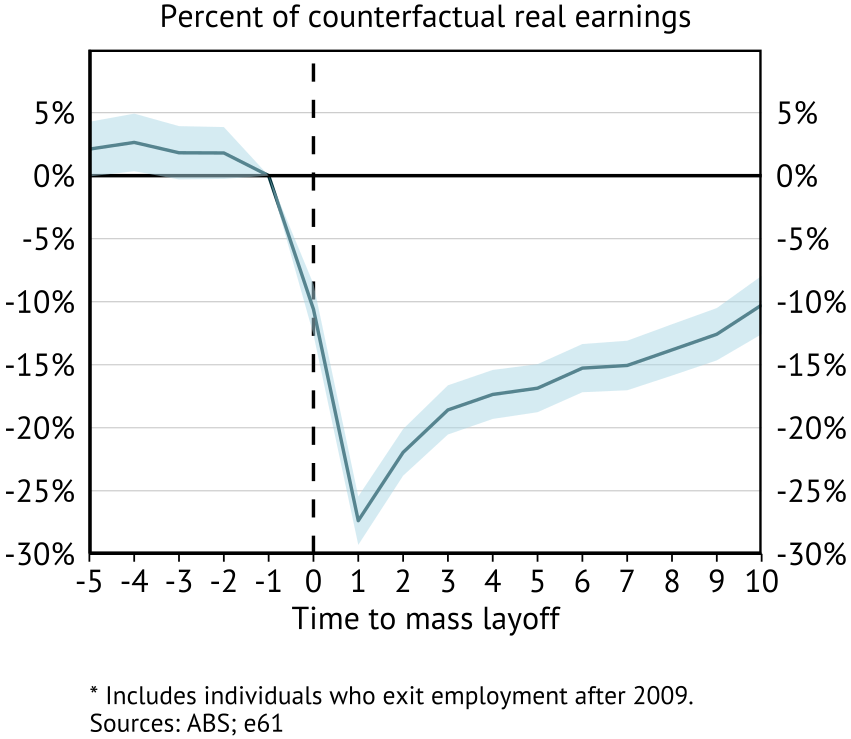

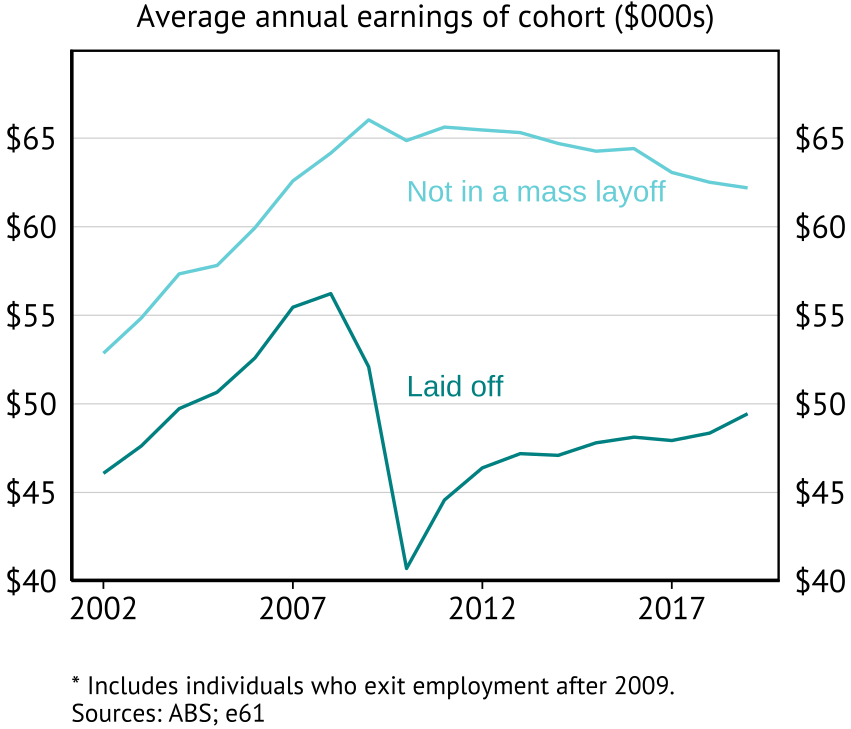

Relative to their expected level, the person who loses their job has 27% lower earnings the following year, 16% lower five years later, and 10% lower a decade later.

What is wage scarring?

Imagine you are sitting there doing your thing, working for your generic employer, doing your generic job, thinking about the great things you’ll do on the weekend.

Suddenly, the government says that everyone who has a tax file number that ends in three has to leave their job and cannot be reemployed at the same employer.

That would sort of suck - but it would be a purely exogenous job loss. After that job loss you would go around applying for jobs, trying to understand what might suit your skills, figuring out if you should move country or study etc etc.

Eventually you would find a job, and over time you would progress in that job and earn an income.

Wage scarring reflects the difference in wage earnings between this job, and what you would have earned if you had not lost that initial job (the counterfactual).

We can work out this counterfactual you by considering what happened to individuals who didn’t have a tax file number that ended in 3, but otherwise look very similar. If you would have earned income in a similar way to them in the absense of job loss then the difference between their earnings and your earnings is as estimate of the wage scar you experienced.

Who cares?

It would be easy to say “this is an important measure of the harm from job loss”, but this is actually a question that requires a bit more.

By just framing this as a measure of labour market costs from job loss, it is easy to just view this as a realisation of labour market risk.

If this is the case, then these job losses are just a product of the world changing and a product of the risk we have in life - in that case any arguments about this relate back to how we feel about self vs social insurance for labour market risk.

However, lets think about some of the reasons why income may have declined for the person:

Time out of work see’s the workers skills become less valuable (loss in human capital).

Technological change has reduced the value of individuals skills (loss in human capital).

The firm was a high productivity/high pay firm (firm value/rent).

The match between the worker and the firm was better than a new match (match value).

The worker was very knowledgeable about using systems at that firm to their best use (match specific capital).

And what about the firm?

The value of the worker had declined, but not the tasks involved in the job (reduced match value).

The value of the tasks declined (reduced job value).

External factors (i.e. credit constraints) forced the firm to end a productive match.

Each of these combinations of reasons why the firm ended the job and reasons why the worker ended up with lower income has different interpretations. Some are just transfers from the worker to other people, while others show loss of surplus that imply this is a net loss in income over everyone.

If we want to fully think through the consequences of shocks that lead to job loss we have a lot of other things to think about. However, understanding the income loss associated with an exogenous job loss helps us start to tease out this problem - and also understand the cost for people who face job loss.

Why do you keep saying exogenous

Fair.

Job matches can end for a whole bunch of reasons. There can be self-selection (i.e. a job-to-job transition or “voluntary” unemployment where the worker quits) or there can be firm selection (being fired).

Self-selection isn’t really our focus, as it is likely people are leaving jobs to get a better job!

Firm-selection also has an issue - as the firm is likely to remove their “least productive” or “worst matched” workers. As a result, they select a type of worker that they were not going to give a pay rise - and so comparing them to other workers will overstate the income loss from this event.

We are trying to isolate the effect due to job loss - not due to selection. As a result, we want to make a case why the job losses we’re looking at do not involve much self-selection or firm selection. Now it is unlikely that we can find a perfect experiment here, but we just need to be clear about this!

What does prior evidence say?

International studies

I’ve already written a lot of words, so I’m going to share a table from Bertheau et al. (2023).

So the five year scars estimated tend to be between 6% and 36%.

What about New Zealand - Hyslop and Townsend (2017) found scars of 13-22%.

The Australian case

There have been a few recent studies in Australia, lets list them out:

Lancaster (2021): Using survey data there was no additional wage scar found after 5 years - involved looking at all unemployment.

Ballantyne and Coates (2022): Using survey data a scar of around 10% was found after 5 years - again looking at all unemployment.

Andrews et al. (2023): A recent e61 piece using administrative data found a 29% scar - focuses on those who are made redundant in ATO data.

Well, what do you all do?

Selection and triggering events

So looking at our piece - specifically the technical appendix - we are looking at a very specific event, influencing a very specific set of firms and workers.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) year.

Firms who have let go over 30% of their employees for a persistent period of time (mass layoff).

Workers that leave a mass layoff firm during the GFC.

Workers who are in their sixth year of work at the same firm (long tenure).

The comparison is then between long-tenure workers who left a mass layoff firm vs long-tenure workers who did not experience this.

What does this have to do with selection? Well a mass layoff helps to mitigate firm selection - as they have many of their workers at the same time.

However, who is to say that these aren’t still the least productive? To help with that we look at long-tenure workers, who have formed a relationship with the firm and where the worker and the firm really know each other.

Results

For most of the results I’d suggest reading the note - it is only 2 pages long ;)

But lets list some highlights here.

What is our five-year scar? 16% of earnings - so the individuals who lost their job in a mass-layoff have earnings 16% lower than expected.

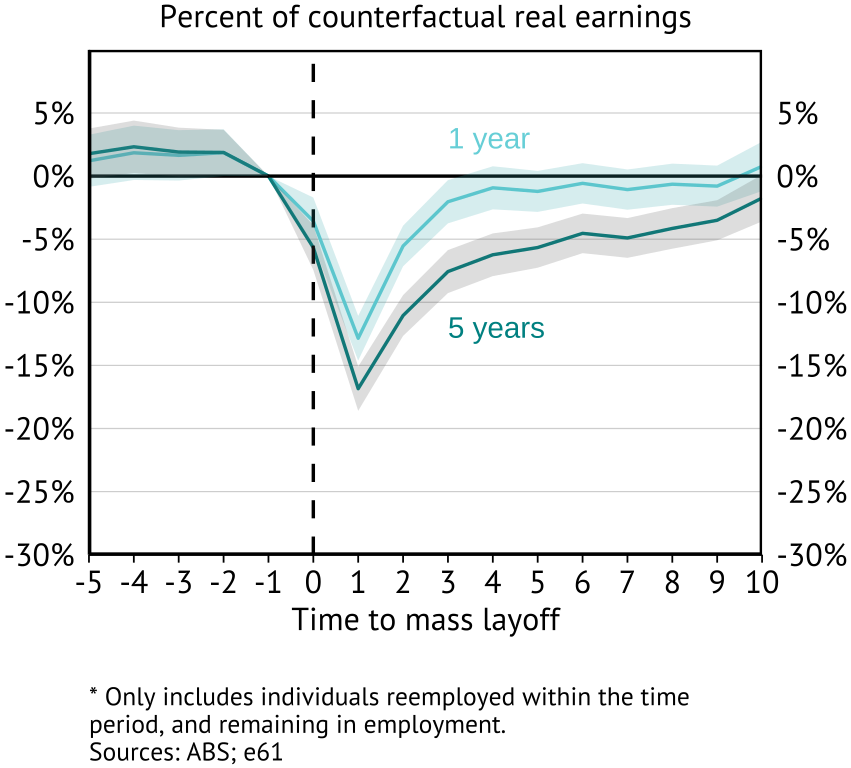

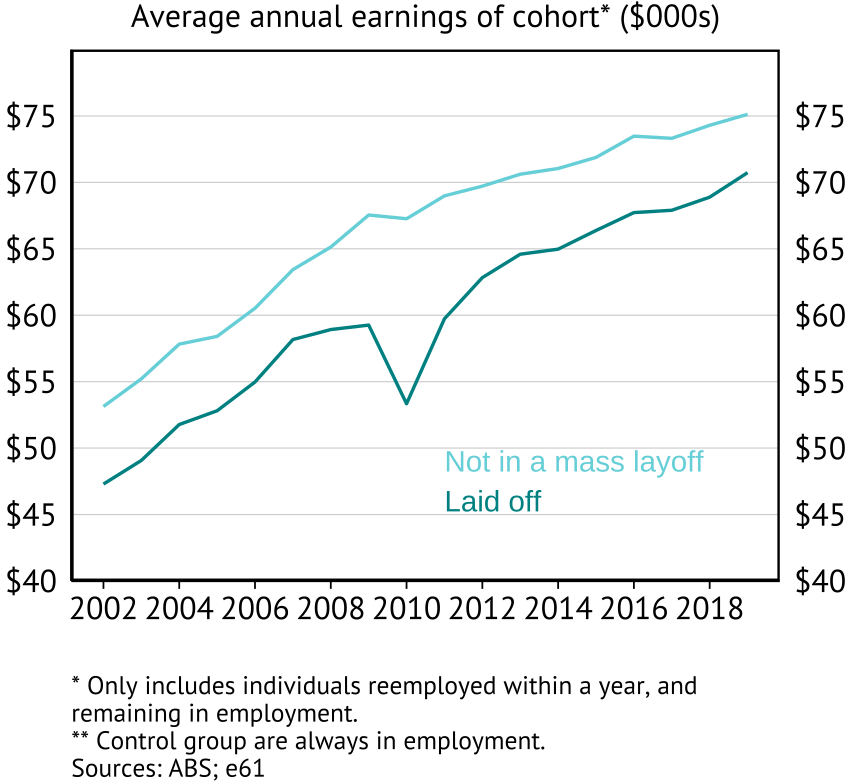

How much is this just about people having trouble getting and maintaining work, as opposed to employed individuals earning less?

Turns out a lot. Those who are re-employed after 1 year (who stay re-employed) have no scar after 5 years. Those re-employed within 5 years have 5% scarring.

Thanks Matt, a very useful analysis. If I am reading your post correctly, then wage scarring on average is driven by those failing to re-attach to the labour market within 1 year. Presumably, those subject to a mass layoff during the GFC faced a labour market with high unemployment. My question: would you expect the same average scarring in response to a mass layoff if the labour market was buoyant (i.e. unemployment was low)?