Assessing benefit eligibility and adequacy

Last week we’d been chatting about the unemployment benefit in Australia and the reasons why some unemployed people don’t get it, while some people who aren’t unemployed do.

Everything boiled down to eligibility criteria – criteria that are intended to exclude those that aren’t deemed to need it.

After realising this, my colleagues and I at e61 were interested in using available data to provide an assessment of the whether these eligibility criteria were effective at this stated aim. So here is the note, and here is the appendix. We also used a similar method to evaluate outcomes for those who did receive the payment.

The key result – judging by consumption responses, there are a group of single Australian’s (likely older and without kids) who appear to go through greater hardship following job loss.

[Update: After setting this post to go up I’ve been sent that the government is going to increase payments for those over 55 – I’m guessing for single individuals. Not the biggest fan of highly bifucated rates, but will wait for the proposal and discuss – and would note that outside of the consumption responses we yarn about the international labour supply evidence on this is quite mixed and hopefully we can comment a bit on Australia in a few months ]

Before jumping to the post I want to note a couple of things:

You might believe that irrespective of means this should be a payment for job loss, or a provided minimum income – in this case you’ll still want to scrap criteria no matter what this research says. And that is legitimate.

You might weigh the costs from individuals missing out much more highly than the provision of a payment to someone who doesn’t need it – in this case you’ll want to dig in further to identify very narrow groups of individuals who may be excluded. This is also legitimate, but the data sources aren’t quite ready to go that deep … yet!

Given this, lets chat.

Eligibility

Given eligibility criteria are largely targeted towards means, it feels relatively simple to just state whether they seem fair or not! There are income and asset tests, and mutual obligation requirements that involve job search components. In this case we’d ask if the income and assets involved in the tests feel like they are at the right level, and whether the cost of job search is appropriate.

This is an important way of looking at the problem, but there is one issue – we can’t observe many of the relative margins where individuals can call on resources to understand how binding this constraint is.

We may observe a low income individual with few assets, but they may have a wealthy family member that helps them through. Or we may observe someone with substantial assets who just cannot access them and is forced into hardship based on insufficient liquidity.

We want to look at a choice that suggests the individual is having to make costly decisions due to the situation they find themselves in – and the choice we can use is their decision about how much they consume.

For a temporary income shock we would expect individuals to try to largely maintain consumption – yes people won’t have to pay for work expenses, and they may be a bit uncertain about future income and so hesitant to spend, but this is the time when people will try to use any access to funds they have to avoid an unnecessarily sharp drop in their spending. We would term this insurance against the income shock.

As JobSeeker is focused on such temporary shocks (where other payments are intended to be for longer term shocks) we can simply ask if people are having to sharply cut consumption when they lose their job. Specifically for eligibility, we can ask if people who do not receive the payment appear to cut spending sharply – as this would imply we are excluding people from the payment, who are not insured against the shock.

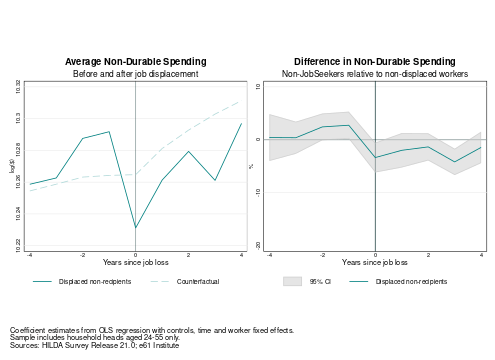

How does this look?

At face value there is a drop, so maybe this group isn’t fully insured. But it is hard to tell without a full description of what their optimal behaviour would look like.

The key result instead comes from looking at subgroups – a 3% decline for couples and a 14% decline for single people, when faced with a similar income shock. It is for this reason that we state there appears to be a group of single people who are forced to adjust sharply to job loss, and hence appear to lack the support networks required to maintain consumption.

Adequacy

Given the above way of thinking about the world, we also saw some potential to consider the adequacy of the payment. Static poverty lines are the typical way for looking at adequacy (e.g. this ACOSS-UNSW report) – often augmented with analysis of the assets individuals have on hand.

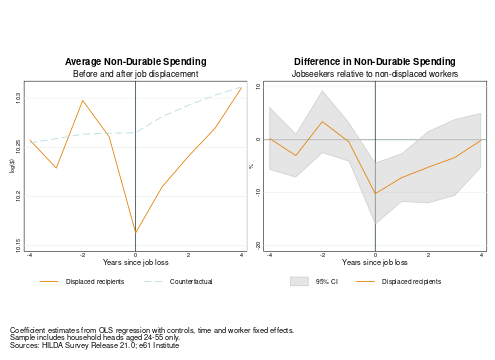

However, the same choice argument applied above can also be used to think about the consumption choices of those who receive the payment. Right so how’s this look.

So the people receiving the payment cut spending as well – same deal, couples drop 3%, singles 16%. In this way, the payment is inadequate to prevent a drop in spending – and so inadequate purely as an insurance mechanism.

Now it doesn’t follow that the payment rate should rise per se – instead it tells us that there are a group of single individuals who do have to cut their consumption sharply on job loss, even when they receive the benefit payment. Depending on how we view this there are a variety of policies that may be appropriate – a higher payment, an income contingent loan top-up, access to superannuation funds, a levy based income insurance system.

The key point is just that there is this sharp response that is concentrated among a certain group.

Consumption has its own issues

In the appendix to this note we go into a lot more detail about the concerns with using consumption as the measure for considering this. By establishing that the income shocks were similar between recipients and non-recipients, and the expectation of reemployment was similar, we have convinced ourselves that this exercise gives some useful insights about eligibility and adequacy.

Specifically, it is clear that – given the current system and incentives faced – single people respond a lot more to job loss than couples do. Single people, especially those without children, are a perennially ignored group in social policy – even though this is the group that is most of risk of social isolation and in some circumstances poorer labour market outcomes.

In the next few months, we hope to be able to say a bit more about labour market outcomes – and how the benefit system may influence these. But for now, keen for your thoughts in the comment section below!