It was fun to see the economist who got me into the discipline - my older brother Patrick Nolan - write about the Iron Triangle of Welfare policy this weekend.

As Research Director at the Retirement Comission he was focused on applying this framework specifically to aged pensions. However, he’s been applying this across the New Zealand welfare state for most of this millennia.

So does this Iron Triangle stuff have anything to do with the Aussie debate about benefit rates and our new enlightened views about welfare being insurance?

tl;dr policies always involve trade-offs. For benefit policy a trade-off between “work incentives”, “payment rates”, and “fiscal costs” is useful for thinking about what happens when we change benefit payments and the way we reduce payments as people earn more (abatement), or use other forms of support. However, when we regulate or compel choices (i.e. mutual obligations) this triangle gets more complicated.

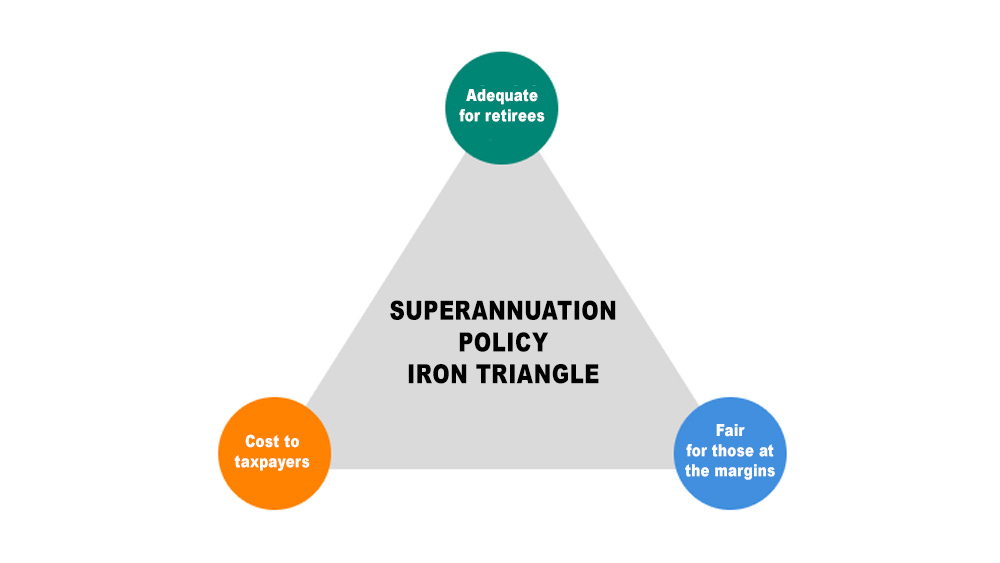

The Iron Triangle

The description of an iron triangle of welfare that defines the policy trade-offs that must be faced is not a uniquely New Zealand description. Richard Blundell made it the centre-piece of his 2001 Keynes Lecture, while politicians like Andrew Leigh in Australia have used it to motivate their decisions around the relative level of the JobSeeker payment.

Let me borrow the image from the article:

So how do I read this? The formal idea is as follows: for a given amount of government expenditure you cannot both increase the payment to those who are not participating in work (adequacy of the minimum payment received) and maintain financial incentives to work.

As a result, we are picking a point somewhere in the triangle - but to move closer to one point (lower cost, greater income, greater work incentives) we have to trade-off against other points.

For payments to those who aren’t intended to “participate” in work the maintainence of work incentives may be unimportant - such claims are contentious (even for aged and severe disability based payments) so my example here would be the high rate of benefit payments during COVID when the goal was for people to stay home.

However, for something like the JobSeeker payment a reduction in work incentives is deemed to be important - whether it be due to concerns about moral hazard driving up the cost of providing support or a poverty trap where individuals become long-term dependent on benefits.

Now economists like to be a bit more specific about what these three elements are, so typically we would say.

Adequacy reflects the level of the payment. Although there may be an “adequate” level, due to policy trade-offs we are normally in a state where the payment is lower than whatever we would deem as adequate in isolation.

Fiscal cost reflects the amount spent on the scheme. If you spend more on the base payment it will cost more - how much more depends on the balance of the increase in payments to recipients, how many more people will take-up the payment due to the increase, and any savings made if there are positive spillovers from the payment (i.e. less crime, lower health care costs).

Financial incentives to work: This doesn’t usually involve thinking about “income effects” - or the idea that someone will simply decide not to work because the benefit is enough. Instead, financial disincentives refer to high effective marginal tax rates (EMTRs) and participation tax rates (PTRs) when undertaking employment. The fact that benefit abatement will lead to a tax rate of 30-40% for moving into a regular job reflects the key disincentive that is considered.

In this world, if we increase the payment to improve adequacy but do not change the fiscal cost, this would mean that we’d need to “claw back” the benefit through abatement more quickly - thereby making the movement into work even less attractive.

You can see how high these disincentives are in the growing suite of tools available in Australia and New Zealand to show it. The New Zealand Treasury Income Tool, and the alpha tool my colleague Matt Maltman and I are building for Australia both illustrate how flat net income gets as you increase your hours of work - or in other words, how little additional take-home pay people get as they try to work extra shifts or accept a promotion.

These sound like empirical questions?

Nice - you raise an excellent point.

The Iron Triangle represents a fundamental set of trade-offs - but:

These trade-offs are a function of the general institutional structure and set of other policies - job training, job opportunities, job search and finding obligations.

These trade-offs are measurable … in theory.

We require a set of values to determine what trade-offs we are willing to make.

We also require value judgements about certain “terminal values” such as what is an adequate minimium standard.

The last one if very important. If someone believed current payments were exactly “adequate” then it doesn’t matter if we estimated a very small fiscal cost and no financial disincentive - the person would still not want the payment to change.

But these last two points are not really my place - they are for you to think about and make your own choices. So I’ll focus on the first two. And as I’m in Australia and I’m getting the chance to look at these issues with a bunch of wonderful colleagues I’m just going to plug some recent insights we’ve pulled.

To judge “adequacy” I’m going to ask a very specific question - does a person have to sharply cut non-durable spending after they lose their job. If they do they do not appear to be “insured” against job loss, and the benefit payment is insufficient to “perfectly insure them”.

You might view this as too generous for adequacy - and that is fine - but it is a start that reveals information from individuals choices. Using this frame, Australian payments look inadequate following job loss. Note: This leads to a bunch of additional questions that we will hopefully answer in future work - and you may see in some presentations we are doing.

To judge financial disincentives to work I’m going to also look at behaviour. We’ve established that EMTRs are high, but do people respond to them? In terms of the JobSeeker benefit it appears not - although if we were looking at the tax system alone our friends at TTPI find that many people do.

Furthermore, any sort of long-term benefit dependence stemming from current payments appears to be a concern that is overplayed - with long-term receipt trending down, contrary to some suggestions.

This does not imply that there are no labour supply responses to benefits - instead I want us to take away two points, points I hope we will be releasing more about in the next six months:

Job search obligations matter - a point that our friends at Melbourne Institute have made forcefully here. If people have to work or will lose their benefit, the real tax rate is not high - but this also implies they may rush into jobs that don’t suit them. The iron triangle strikes again with another policy trade-off … or perhaps “job quality” turns this into some type of iron square.

Behaviour depends on the level of the change - a small change in the benefit level when it is low will have a different impact that both a large change, and a small change when the level is high.

This is dumb - a welfare payment is paid for by your taxes, so it is insurance

I have sympathy to elements of the idea of viewing benefit payments and taxation as a form of insurance - where you expect to receive support if you experience bad luck associated with job loss, or poor health.

But the Iron Triangle is not disputing that. By making the case that the benefit is a shared experience, that the welfare state is insurance, that a minimum income is a human right, you are making a case to motivate the public to increase the fiscal envelope they are happy to provide to the scheme.

You are convincing people about the scope, size, and placement of this safety net.

But then, when you have the fiscal constraint associated with what people will fund you still face the same set of trade-offs between adequacy, cost, and the incentive to return to work.

If raising insurance feels random to you, then that is all good - just ignore what I’ve just said. However, the language of insurance and the view that the social safety net provides “social insurance” that replaces some of the need for private savings and community support is common - and reasonable.

And it is fully consistent with the Iron Triangle.

The language of insurance does change one thing - we start to see adequacy as less about a minimum standard, and more about what someone previously earned. Adequacy stops being about targeting efficiency for a payment rate and becomes solely about replacement rates - if these are topics you’d like to hear discussed more comment below.

This is a different view of adequacy - and one that is quite consistent to the estimates we have above based on consumption responses (and the broad Baily-Chetty framework). But personally I think the redistributive motive - the minimum standard a citizen can expect - is something should keep front and centre when thinking about such schemes.

But even if you disagree - even with this new view of adequacy the Iron Triangle still exists, as income insurance still suffers from work disincentives (moral hazard) and the conflict about what levy/fiscal cost to set pay.

I appreciate your detailed attention to the nature of trade-offs WITHIN the iron triangle. It's useful stuff, so long as we also raise our heads from time to time to remember that we can always step OUTSIDE the triangle by using better taxes.

We don't need to agonise too much about optimising within an arbitrary constraint (though I appreciate that it is intellectually fun). Optimising within the whole choice set is more important.

Not coincidentally I have a report which frames land taxation in just that way.

Short version - if other states taxed land like the ACT, we could pay for all welfare taper rates to be halved. That would mean an effective tax cut of 20-30 cents in the dollar for over one million workers and extra cash in the pocket for around two million more.

In that context, mucking around within the iron triangle is just fiddling at the edges.

https://www.prosper.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/2024_Prosper_EMTR_Report_Web.pdf