In the last few weeks we’ve done a couple of reflections on the five year anniversary of the COVID pandemic (lead up to the pandemic, lead up to lockdown). Today we’ve got a special one though - the five year anniversary of the JobKeeper policy.

At the time this came in I was in New Zealand - so I have no special feelings about the program. However, talking to Australians this policy holds an almost mythological place in the Australian COVID response.

So I have to give a content warning that I will be talking about this policy as an emotionally detached Kiwi - who believes the introduction, design, and exit from the equivalent scheme in New Zealand was arguably better. And where analysis of the scheme has been willing to be critical (with detailed independent economic analysis and CBAs).

Note: There are a lot of economic things Australia does better than NZ - hence why incomes are 30% higher - but let me claim something here.

But as this is a retrospective I also want to be clear - JobKeeper was a big plus in the context it occurred in. It was a brave policy that was a massive net positive during a time of great uncertainty, when it was unclear if other policy options were even possible/feasible.

Admiting that such a policy was done in a rush, and could be done better if we are willing to evaluate and plan for the future, does not undermine this.

So what are some lessons I think we’ve learned? I’ll list these below but remember this is just my view and arguments, others will have different lessons and may have better arguments.

If that is you feel free to outline them in the comments below. And I’d be remiss not to point to the series of Independent Australian reviews that have discussed this topic - like this one, and this one only on JobKeeper, and this one, and finally this recent book. I don’t see anything I’m saying here as contradictory to all of this rich work.

tl;dr Long post - so the summary lessons I’ve taken are:

When you use job retention schemes during a natural disaster type crisis, the benefit comes from moving quickly.

Have a clear exit. Once the worst of the uncertainty has passed exit quickly.

If the institutional structure allows, focus more on direct business and household support that targets the shock at hand - rather than maintaining job matches.

Invest in the infrastructure to provide support to households and firms so a wage subsidy is not necessary in the future.

JobKeeper and other policies

On March 30th 2020 the JobKeeper scheme was unveiled. This was 7 days after the announcement of an Australia wide lockdown and the second series of COVID policies (JobSeeker expansions and payment increases, tax adjustments).

This was a full 13 days after the New Zealand equivalent scheme had been implemented on the 17th.

I had nothing to do with the design and introduction of the New Zealand policy, other than being in the room of the people who were working around the clock to set it up.

Those that stood up this policy buried themselves into the work with an incredible desire to support their communities through a true global natural disaster - and exactly the same thing will have happened with JobKeeper in Australia.

In New Zealand policy makers had the “advantage” of the Christchurch earthquakes. This provided a roadmap for the use of wage subsidies during a natural disaster. So once the pandemic was officially announced it could be whipped out.

This also led to extremely high levels of uptake.

Another country took another approach which - at the time - was seen as madness. The US and PPP loans. The US policy interventions were less interested in retaining job matches, and instead wanted to keep households and businesses solvent through the crisis.

As a result, the PPP scheme was not introduced until 24 April, and took the form of a concessionary business loan for general expenses based on payroll. It did have retention properties with forgiveness rules based on retaining a portion of workers on payroll.

This scheme was much more untargeted and thereby deemed to be expensive and regressive in the initial evaluations (although this view is improving). Fraud has been a lasting concern, and the need to introduce such an untargeted policy due to gaps in infrastructure is itself a concern.

On one level the US shock was quite different - as they did have a genuine large outbreak of COVID. But by the policy logic in Australia and New Zealand at the time this would have increased the rationale for such a subsidy.

So we had two key design differences - New Zealand moved faster than Australia, and the US did not move at all. How did unemployment play out during the crisis? Well … those two weeks look like they had a big effect.

Lesson 1: When you use job retention schemes during a natural disaster type crisis, the benefit comes from moving quickly.

The exit

The JobKeeper scheme ended at the end of September 2020. Just to start again for six months. So it ended in March 2021. Just to get extended in NSW with the JobSaver scheme … you get the point.

Australia struggled with its wage subsidy exit strategy.

How about New Zealand? Three months. Short-term wage subsides were allowed for regional outbreaks, but these were very focused schemes - and were cut down and debated.

I was still in New Zealand at the time and I’ll be honest. I was Edmonds-Hamilton-Preston pilled and was petrified of the wage subsidy ending so quickly - I was certain this was a massive mistake.

Just like in the Conversation article I felt like wage subsidies should stay in place while the make-up of the policy settings were adjusted towards more standard supports. And my old work colleagues, who I share a lot of views with, believed that same.

Luckily I had nothing to do with anything, and those providing advice and taking advice in New Zealand recognised that there were real costs from stopping individuals from making productive job moves.

And they were right. Unemployment increased but did not surge, individuals were once again moving jobs based on the actual opportunities at hand, and support could become more focused on preventing illiquid but solvent firms from failing, and making sure households had adequate income.

NZ research found that the cost-benefit of the scheme that was in place was over 1, but dipped under 1 for the mini-schemes introduced during “resurgences”.

Furthermore, Australian research has pointed to the benefits of the scheme being concentrated in the first couple of months - and the costs increasing as the scheme went on. This holds for both the employment effects (with related estimates here and here) and for the productivity effects.

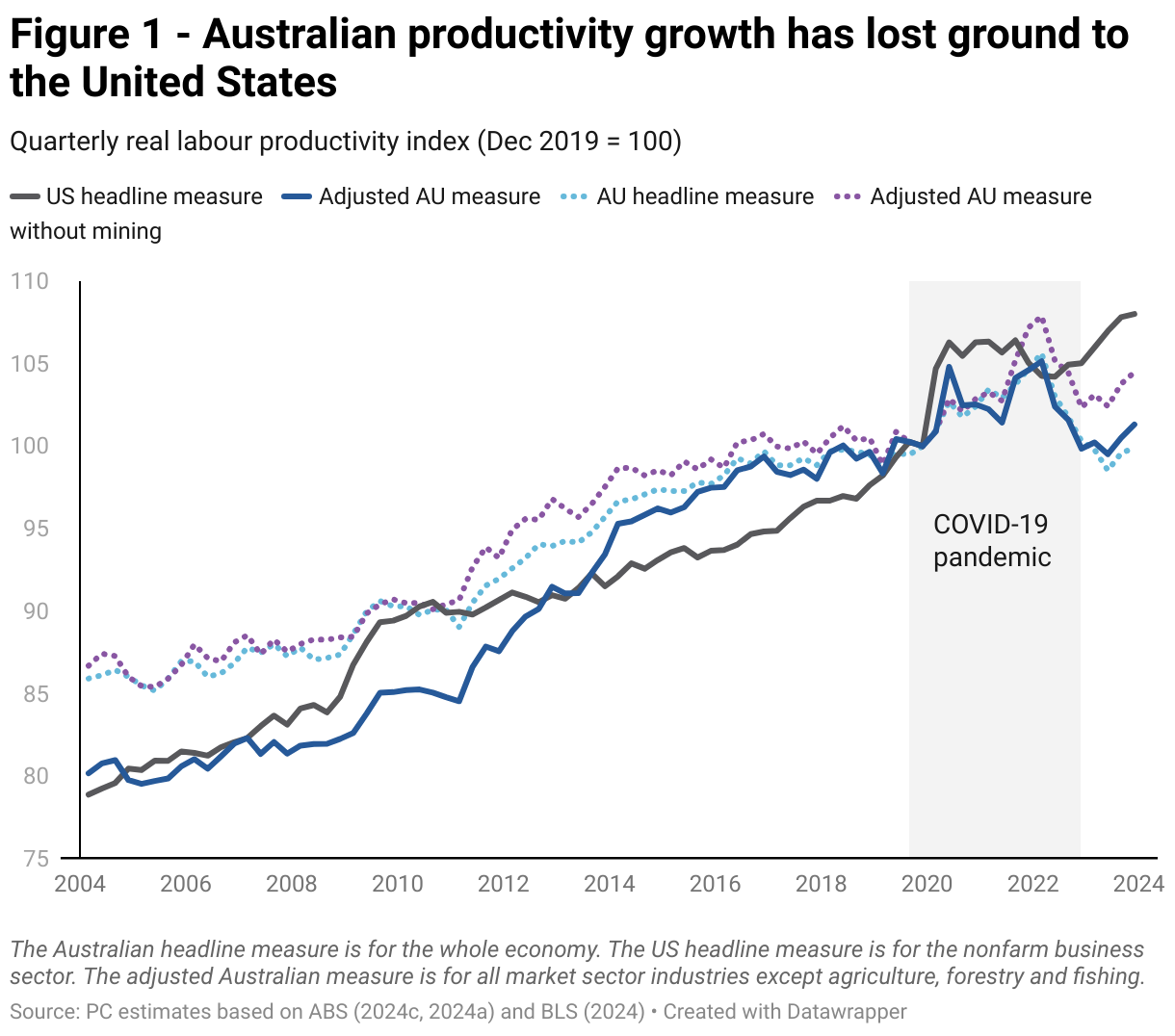

Coming back to the US, NZ, and Australia comparisons - productivity growth in the US has exceeded both countries. If the lack of a job retention scheme did threaten productive capacity, then why has this happened? (via the Productivity Commission)

This is not to go as far as saying JobKeeper may have driven persistently lower productivity (i.e. one reading of the Productivity Commission). But the “benefits” in protecting productive capacity appear to have been overstated, while the “costs” in preventing job reallocation appear to have been understated.

Lesson 2: Have a clear exit. Once the worst of the uncertainty has passed exit quickly.

Alternatives and the outcomes of JobKeeper

The restriction to job mobility captures the core benefit - and cost - of such a scheme.

To understand this we need to ask - how is a wage subsidy different from providing income support to households or concessionary loans to businesses?

I have a picture here from my colleague Lachlan Vass that explains why:

So we do a wage subsidy - instead of other policies - if we believe there is some lost match value that will be destroyed if people separate.

Note: Now, we are assuming that - in the absence of a wage subsidy - we would provide liquidity support for firms and income support for households. If we were not going to do this, the calculus would be different.

So lets think about separation.

For a wage subsidy to be the right policy, for some reason workers and firms that are really well matched together need to separate. And then these people cannot find each other again in the future.

As time has gone on, this argument has made less and less sense to me.

If the job is really valuable to an employer, then as long as they can stay afloat they won’t fire the person. If the job is very valuable and they separate for a short-time, then the employer and employee are able to contact each other - and get back together to do their beautiful work if they need to.

If you both want to work together, is it that hard to agree to get back together?

The idea that employers and employees will be randomly thrust away from each other, to never return again, just doesn’t make intuitive sense - and definitely does not match the US experience.

Furthermore, in Australia we find little evidence that the match quality of JobKeeper supported jobs was particularly high when looking at worker outcomes following JobKeeper.

Our logic for this was two fold - a description of the prior earnings/tenure of jobs and the outcomes in terms of retention and wages. If there was substantial value in that match we would expect the match to be retained going forward and a wage premium for doing so - neither of which were observed.

Secondly, we also roughly estimated the match effect in an empirical approach and looked at the distribution of these match effects among those who received JobKeeper. These effects were similar to other jobs in the economy.

The justification for a relatively limited match effect mirrored our discussion of Whyalla Steelworks and the growing literature on such effects.

However, I don’t want to overstate the strength of our evidence - COVID was a specific shock, and overreactions to uncertainty combined with congestion externalities in labour markets could themselves be a big concern. But I have not been sold on that case … yet. As has been stated, understanding the role of such schemes is an area that needs more research.

Lesson 3: If the institutional structure allows, focus more on direct business and household support that targets the shock at hand - rather than maintaining job matches.

So no JobKeeper ever?

No no. JobKeeper met its goals in a crisis. Current evidence on improvements is only partial and more work should be done. We know the system works well through the ATO. Finally, the public understands the system, and there is political and social goodwill to the scheme.

If there was a pandemic right now and Treasury kidnapped me to force me to write advice on what should be done, the JobKeeper program with some adjustments (namely a very clear set of conditions for ceasing the scheme) would be an option - and it would be one of the preferred options.

But if we can build up the infrastructure for providing support to households and businesses directly, it begins to look more attractive to do that directly.

Wage subsidy schemes are not a first best policy for the intervention we are trying to achieve during a pandemic. They are a policy of convenience due to limits in state infrastructure.

We should invest in the administrative state now - improve IT, lift the size and capability of the public sector. It served us well during this crisis as noted in a recent book about the pandemic, but it can still serve us better.

So this gives a clear lesson 4: invest in the infrastructure to provide support to households and firms so a wage subsidy is not necessary in the future.

All that makes sense to me Matt

Beautiful policy compared to doing nothing, put together fast

But lack of clawback provisions and exit strategy definitely hurt (media scares every time we tried to end it were incredibly frustrating)

Key is to learn lessons for the future

At the time it felt like Frydenberg was using COVID as a pretext to prolong the stimulus in order to win the 2022 election.