A recent article in the AFR by John Kehoe discussed the clear weak productivity performance in Australia since the pandemic - and makes the case that having such a long wage subsidy during the crisis may have had a long-lasting productivity cost.

In the article he discusses some descriptive work that I’d undertaken last year with my colleagues Dan Andrews and Lachlan Vass, which - when combined with separate pieces of research from Dan (Andrews, Bahar, and Hambur (2023)) and Lachlan (Bradshaw, Deutscher, and Vass (2023)) - suggests that the later stages of the JobKeeper program kept individuals tied to unproductive jobs.

JobKeeper was a crisis policy - it was a brave policy that helped Australia through a crisis, and was a hell of a lot better than doing nothing! However, the AFR articles desire to ask if there have been unintended consequences - and whether, next time, we might do things a bit differently, is exactly the right way to talk about policy.

If we can’t learn from our experience, we will undertake policies in the future that hurt people under the guise of helping them. Surely we are better than that.

So I thought I’d talk about some of the ideas here - and of course happy to discuss in the comments.

What has happened with labour productivity?

Nice question. Lets look at some data.

This shows labour productivity (GDP per measure of labour input - in this case either hour of work or employee numbers). The squiggly data is the actual data, while the smoother lines are fitted trend lines.

There are two key take aways that people are discussing:

That smoothed line has gotten pretty flat since the mid-2010s!

The squiggly line spiked up during COVID, and then has fallen sharply since. Overall this squiggly line is below its trend level.

So we have two points we want to explain - why has trend labour productivity growth fallen to zero (so labour productivity has not been rising) since the end of the mining boom in the mid-2010s? And why is labour productivity below its trend level now in the post-COVID economy - especially given the surge observed during COVID?

These are active puzzles, and Andrews and Hambur (2023) does a good job of breaking a lot of this down. They note that the reallocation channel for productivity growth has broken down - with capital flowing to less productive firms and workers remaining at less productive firms.

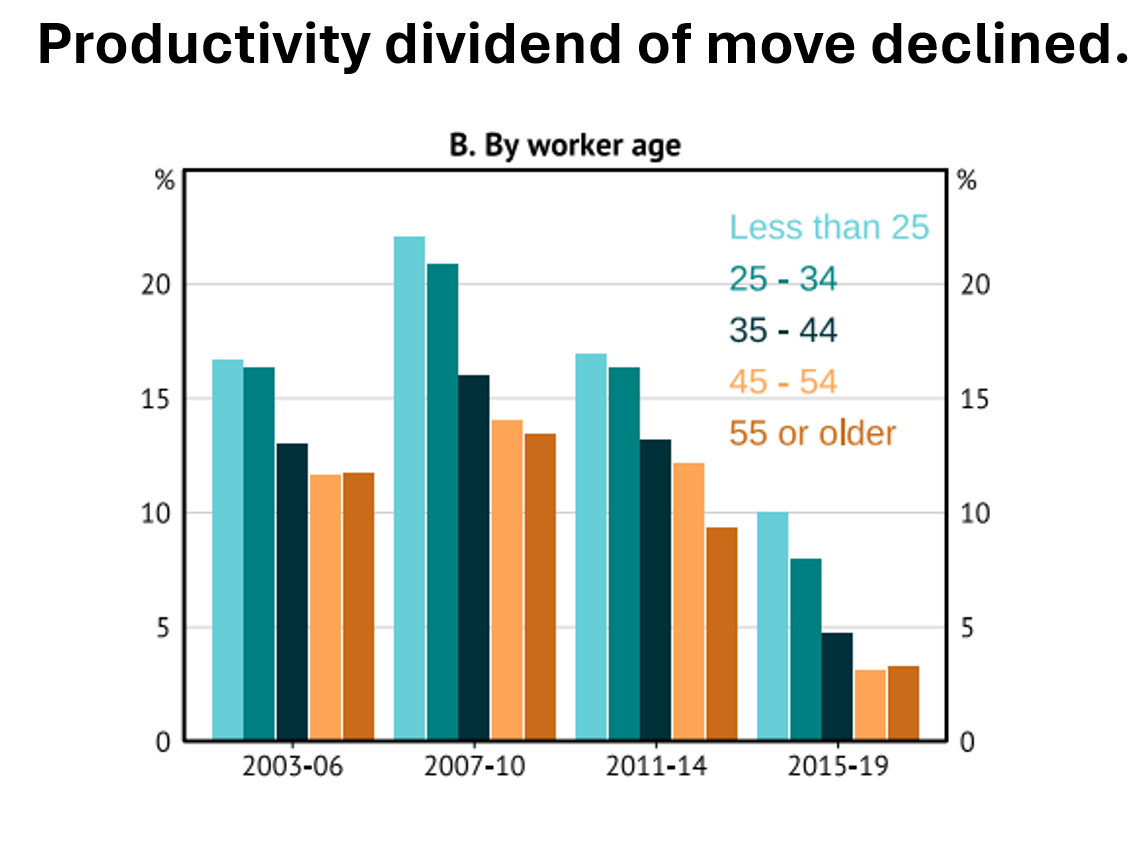

Work by Jack Buckley and Aaron Wong added to this - on the productivity side it appears that individuals that have been moving firm have received less of a return for doing so.

These pieces of evidence all speak to a situation where there are increasingly barriers to individuals working at a place that makes the best use of their skills and know-how - a situation that was binding prior to COVID.

And then, our response to the pandemic was a wage subsidy - to stop people moving.

How does a prior wage subsidy relate to productivity now?

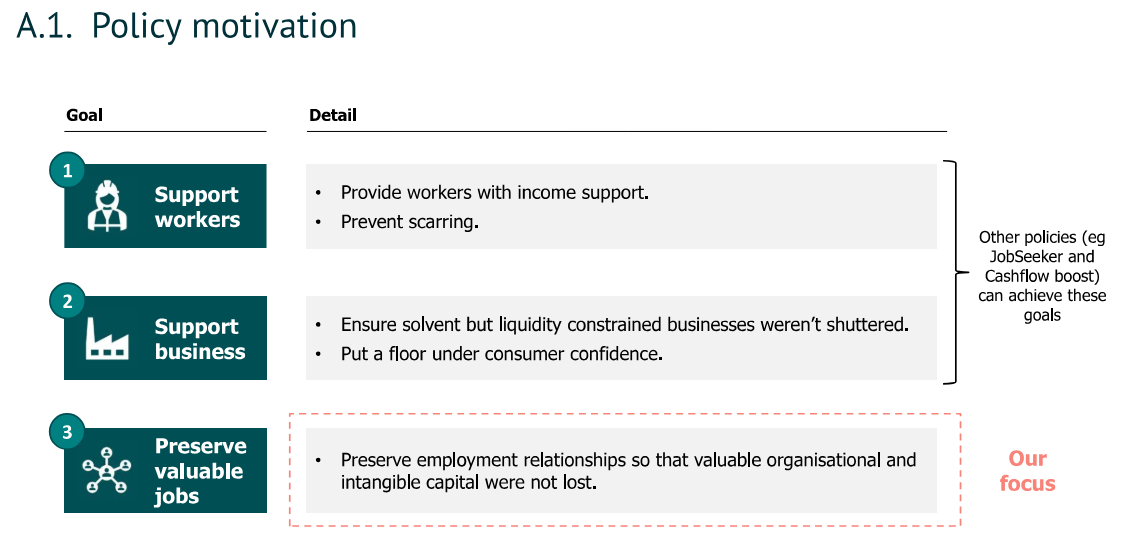

JobKeeper (a wage subsidy) was introduced in the early stages of COVID to stop firms and workers separating from otherwise valuable job matches.

As the COVID review notes, this was a period of intense uncertainty where employers may fire workers or employees may quit jobs without fully accounting for the costs and benefits of doing so. Tying workers and firms together to “maintain productive capacity” was seen as a way of preventing a sharp drop in productivity due to the crisis - and more broadly supporting social cohesion.

Here the idea is that the wage you might earn depends on a number of factors - and a key factor is the firm you work at, and the specific skills and know-how you have for doing things at that firm. This is often termed match value. And the key reason for using a wage subsidy - rather than giving firms and workers cash - was to preserve valuable job matches.

Usually, firms and workers would largely take this into account - as they both benefit from producing more together. But in the first weeks of COVID there was a crisis of confidence with a lot of reasonable people concerned that the world would collapse around them.

However, after three months it was clear that the crisis in Australasia was quite different to overseas - and these economies were opened up. This led to New Zealand ending its main wage subsidy after three months, and focusing on other support.

Furthermore, the US - which was experiencing significant COVID outbreaks - relied on income support for households and subsidised loans to businesses, without the push to retain job matches.

It was Australia that continued to use a wage subsidy long-term.

The ending of wage subsides in New Zealand was predicated on concerns that such schemes force workers to stay at firms that aren’t great for them - to be tied to a sinking ship. With the nature of jobs and work changing after COVID, individuals needed to be able to change employer. In New Zealand the view was that the benefits of moblity would exceed any costs associated with a loss in the special value of a specific job match.

Australia decided to keep this wage subsidy going through for another nine months until March 2021 - creating a strong financial incentive for workers and firms to remain together even if better options were available.

Can you prove a link to productivity?!

No. The evidence provided in our note is descriptive - we simply asked about the indicators that certain job matches were very valuable. Here we focused on whether they were jobs people had spent time building a relationship in (high tenure), whether people stayed in the jobs because they were good matches (higher job retention), and whether there appeared to be a premium for individuals in protected jobs (higher income growth).

As nothing showed up, except for weak wage outcomes for those on the “long” version of the JobKeeper system, the match value argument itself appeared overplayed. Similar to the results found for the shorter wage subsidy in New Zealand (Hyslop, Mare, Minehan (2023)).

Andrews, Bahar, and Hambur (2023) provides a bit more detail here - showing that, in the later phased of JobKeeper, the policy appeared to undermine creative destruction (individuals moving to productive firms, unproductive firms dying).

So by preventing productive job movements this may have had a negative effect on job matching in the economy.

However, it is also easy to overstate this as the driver of productivity right now.

As we’ve shown, a sizable chunk of the matches maintained due to JobKeeper did end in relatively short order after the end of the policy. These individuals will have moved to different employers, or to different opportunities in their life.

And this type of mobility is a good thing for the person, and generally a good thing for measures such as productivity.

Hence if it was solely about JobKeeper we would have expected an initial drop in productivity, followed by a rebound after these workers were unleashed - the policy may hold down the level of productivity somewhat (i.e. by delaying when individuals can invest in new skills in a better job), but it would be rising now not falling.

In this way it isn’t the length of JobKeeper that would explain declining productivity now in isolation - we would need other barriers to job mobility which hold individuals back from finding good job matches.

Here the concern is more likely to be around:

Monopolistic labour markets,

Occupational licencing regulation,

Dismissal regulations and the nature of contracts (i.e. non-competes),

Other policies that can restrict household mobility - hello housing.

And outside of these causes it may be a general technological/global trend - as similar trends have been seen in similar countries.

The OECD graph above indicates that, although Australian outcomes have been a bit worse - there is something happening globally that is leading to weakening labour productivity. Even the start performer, the US, has had only 7% growth in the US in seven years.

Coming back to labour market flows - the rebound in mobility observed post-COVID (Black and Chow (2022)) has still led to job-to-job transition rates that are well below those observed 30-40 years ago in Australia. In this way, the “wage earners welfare state” that underlies Australian policy settings has continued to become less dynamic - and understanding why this is the case is essential to ensure that Australian’s have the opportunities and labour market outcomes that they deserve.

Is this due to the changing nature of work, is it due to policy settings that have become constrictive, is it due to the unusual design of our work/income safety net, is it due to growing labour market power by firms? Each of these would suggest a different policy response - so teasing out the why is going to be pretty important!

My favourite post. Do you have an idea how we can actually measure the value of a match?