What does the unemployment benefit tell us about unemployment?

A recent article (update: now scrubbed from the NewsHub website) discussed how unemployment in New Zealand is mismeasured, as the number of people receiving the unemployment benefit is much higher.

This has been a talking point in public for as long as I remember, and a number of good economists have spent time explaining to me why - although this seems like an obvious point - it doesn’t necessarily follow.

So rather than relying on top NZ economists on Twitter to explain this, I thought I’d work through it myself.

tl;dr you don’t have to be unemployed to receive the unemployment benefit - and you a lot of people won’t get the unemployment benefit when they are unemployed - so we need to understand why benefit numbers have changed to make any claim about unemployment measurement. No-one appears to have done that.

Article arguments

There are two claims that come out in the article. Both of these seem sensible at face value, and as it is a university professor (Ananish Chaudhuri, twitter) stating it it is easy to trust.

Unemployment is “understated” by the unemployment rate - as the measurement depends on someone searching for work and being will to work now at the current wage. Having more people on the benefit than on unemployment tells us these search critiera are missing people.

The jump in unemployment benefit receipt (relative to historic trends) suggests that the undermeasurement is larger now - and that the benefit system is stopping people from working.

Now people have gone pretty hard on this - pointing to a great Stats NZ piece. Ultimately, the unemployment benefit and being unemployed are VERY DIFFERENT THINGS - it just turns out anything economics related is just given a bad name.

To understand this we want to have a bit of a look at the data.

Unemployment and unemployment benefits

A lot of people have said this is fundamentally wrong because the reason for being “unemployed” and the reasons for receiving the “unemployment benefit” are actually very different.

For example, say you lose your job and your partner is in a high income job. You are searching hard for work. You are unemployed - but you can’t get the benefit. [benefit targeting on family income]

Say that you have a temporary medical issue keeping you out of work, so you couldn’t start a job right now and rely on government support through the JSP. You are not unemployed, but you are on the unemployment benefit. [meeting obligations due to temporary incapacity]

Say that you are working and not earning much. You may well receive the unemployment benefit even though you are employed!! [meeting obligations due to work, and insufficient income]

In fact, the two groups are extremely different - see here for the NZ perspective and here for the Aussie perspective. And according to OECD work there is also a bit of a difference all around the world! This is discussed in more detail here - but I’ll throw in a picture that shows how damned different the categories are regardless.

This tells us that you may have more people receiving the unemployment benefit for very different reasons than more people being unemployed - only 25% of people who are unemployed are getting the benefit, and only a third of people getting the JSP in Aussie are unemployed. And the NZ case is pretty similar!

But where some of the online venting has gone a bit wrong is that it doesn’t ask the question - do JSP receipt and unemployment benefits move in the same direction? If they normally do, then a sudden surge in JSP receipt may tell us we are under measuring the unemployment rate … or it might not!

Even if they don’t measure the same thing they might give us some useful information - and the UoA academic might be just trying to explain this in a simple way.

Why has JSP receipt held up in Australiasia?

This is actually a pretty open question which our pretty Venn Diagram doesn’t help with. But it is something where a bit of microdata work can help. To understand the hypothesis that unemployment is understated and that the JSP figures could be telling us something about that we can take two approaches:

Dive into the unemployment survey questions, and look how unemployment changes if you relax some of the assumptions about questions.

Dive into the benefit data, including applications and acceptances, and see if acceptance criteria have changed - if they haven’t it may signal higher unemployment, if they don’t it may signal greater benefit access .

The last piece of work also clarifies that the second argument - that the benefit system is restricting job reentry - has a LOT of extra assumptions. For some reason we have people who are not saying they are unemployed, but are willing to work, but only aren’t because they receive a small benefit payment.

As a result, I’m going to ignore the second hypothesis which is a pretty sizable overreach, and instead just try to understand the first.

We’ve had a few people write things in Australia and New Zealand on JSP numbers staying high post-COVID. Bruce Bradbury and Peter Whiteford for Australia, and then Michael Gordon and MSD in New Zealand.

These are great. But none of them really answer our question. They tend to find a mixture of:

Individuals who are unemployed are now more likely to “take-up” the benefit - which may be due to agencies approving, or people normalising applying for the benefit.

A record high proportion of individuals receiving the payment are “NILF”.

If we believed that individuals coming into the benefit were “the same” in terms of work readiness, then yes this tell us that unemployment is higher. However, if it is low income NILF individuals who were precluded from the system that are now in receipt - and who were fundamentally unable to work - then it does not tell us anything about unemployment.

Ultimately, these things are quite complicated - and it is a real reach to say “real unemployment is higher” because benefit numbers are higher, especially given the alternative explanations due to COVID (i.e. bringing excluded individuals into the system, an easing of access).

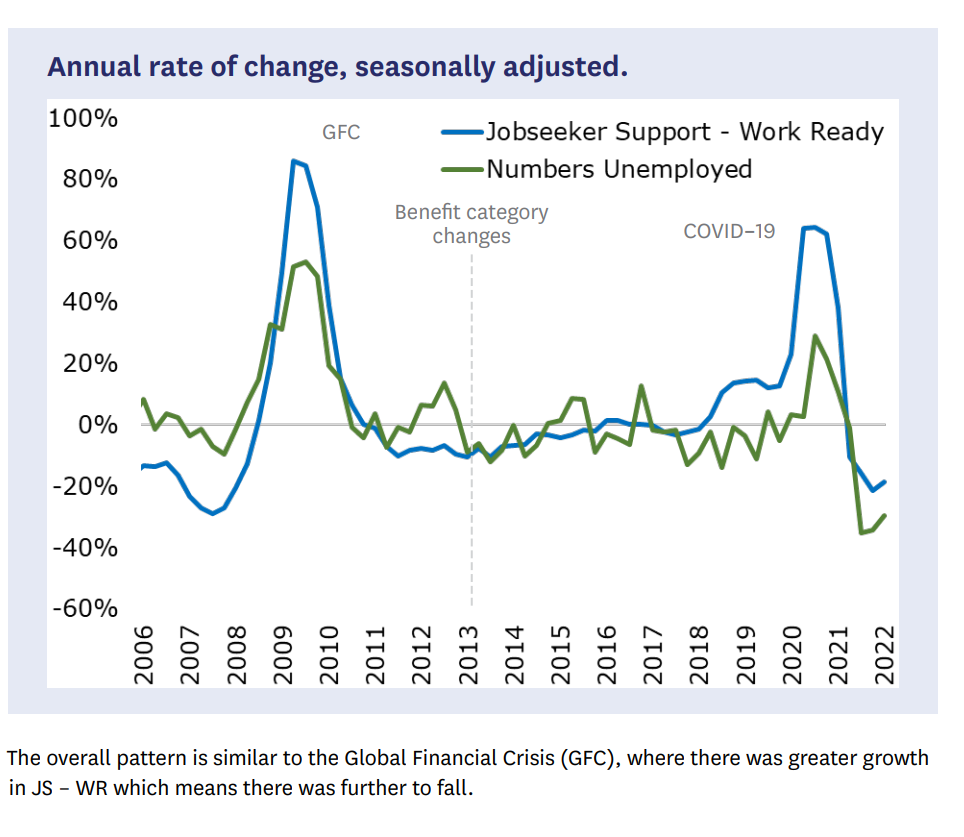

But I also haven’t seen either side actually argue the claim of “do published JSP numbers predict unemployment numbers”. The MSD plots suggests that - pre-COVID, excluding policy changes - it did. And my own unpublished work for 2012 also suggested it did.

So although I think Dr Chaudhuri’s article overreached, and went too strong on conclusions, the real critique is “this is complicated and we need to look more carefully” rather than “no benefit receipt and unemployment are different idiot”.