International student caps ... why?

I was pretty surprised to hear about the bans on International student numbers, and how they are being motivated by “cost of living pressures”.

But no doubt someone has thought hard about this, so I thought I'd talk through it a bit. I haven’t been able to find much analysis, so very keen to hear your thoughts about the issue and any analysis you’ve found that convinced you for or against the policy.

Disclaimer: In my job at e61 I am associated with Macquarie University, and I spent a few years teaching at Victoria University in Wellington. However, my pay and career does not rely on anything associated with any universities and any views I share here are genuinely my own.

tl;dr export education is a large export sector for Australia. Placing these caps across universities will restrict this export market, involve sacrificing important links with the rest of the world, and appears to have limited effect on near term house prices or rents.

Is this about permanent migration?

A useful starting point is to not confuse this with views about permanent migration.

Permanent migration is all about determining the “right flow” of eager individuals who want to join Australia such that the population growth is manageable under current constraints.

I'm a 100 million Australians, 20 million New Zealanders sort of guy. I want more people around to share ideas, thoughts, and undertake unique adventures and activities. Although we sometimes here concerns that such migration will lower wage opportunities for those living in the country already - the Mariana boat lift shows this isn’t the case irrespective of migrants being a “skilled or high type” - a weird obsession in Australasia (especially given complaints in both countries about low fertility and lacking scale for knowledge industries and self-sufficiency).

But we can ignore this debate, as we're actually talking about service exports.

Selling education and a lifestyle

International students are coming here because they are eager to build their human capital, and they are attracted by product that is being offered in Australia.

As a result, we should think about this industry as an export service industry. Where this differs from other exports (except tourism) is that it increases demand for goods and services we normally view as “non-tradable” like domestic housing, haircuts, and parking spaces.

So lets scoot around and find some numbers on this.

According to the Department of Education there were nearly 544,000 international students in Australia on 1 April 2024, and nearly 778,000 enrolled in the year-to-date up to April.

However, the cap is on “new student enrollments” - not the stock of enrollments. Furthermore, it is on Higher Education and VET - not all student enrollments. So looking at the pivot table, there were near 400,000 new commencements in 2023.

BUT, the cap is applied even more narrowly than that. Specifically in this ABC article the 270,000 cap is stated to be 53,000 below the prior years level and 7,000 below the pre-COVID level. Implying that inscope institutions and relevant non-citizen/resident student numbers must be around 323,000.

None-the-less, this is a 20% drop in student numbers - and given it is likely that student numbers would have continued to grow, this is an even larger restraint on this export.

Viewing students payments on both tuition and goods and services when they are here as “exports” - which they are - this is Australia’s fourth biggest export sector. Furthermore, the exports are highly concentrated in NSW and Victoria - although relative to the size of the state economy revenue from export education is largest in Victoria followed by ACT, then NSW, Tasmania, and South Australia (with the relative size in Western Australian and Northern Territories much smaller).

However, the indicative constraints (cheers to Lachlan Vass who flicked this and a bunch of reading across) suggest very unequal treatment in terms of where the limitations bite.

Universities with the facilities and experience supporting large numbers of international students are having their caps slashed, while random regional universities are given large caps … which they probably won’t fill.

Australia is in an international market for students. Students are not thinking “I want to live in Australia, given that I will go anywhere” - they are thinking “I am choosing between these different international universities”. If regional universities could already attract students they would - the pool isn’t scarce - as a result what will happen instead is the students will just go to a different country.

As a result, the “fair allocation” argument is a mixture of nonsense and strangely insular. To attract international students you have to offer them a service - and this policy punishes the universities that can do that (due to scale and location also) for no real reason. This makes it more silly than just some blanket cap - but lets think about some of the broader concerns that may be driving this.

“Spillovers” from scale

So a lot of the complaints are about increased cost of housing due to the areas which are attractive for this service. This was the focus of the initial policy announcement. I will focus on this and not “shonky services” which is the new rationale - as a nationwide cap is completely unrelated to imposing quality standards on courses, to the point where even acting like this is a rationale is ridiculous.

With housing we know that students tend to live near the place they are studying. Is there any way we can view this?

I had trouble finding very much. The Property Council of Australia with the Student Accommodation Association did provide some useful figures - but these are two bodies that you would expect to say i) don’t limit demand ii) build more student accommodation.

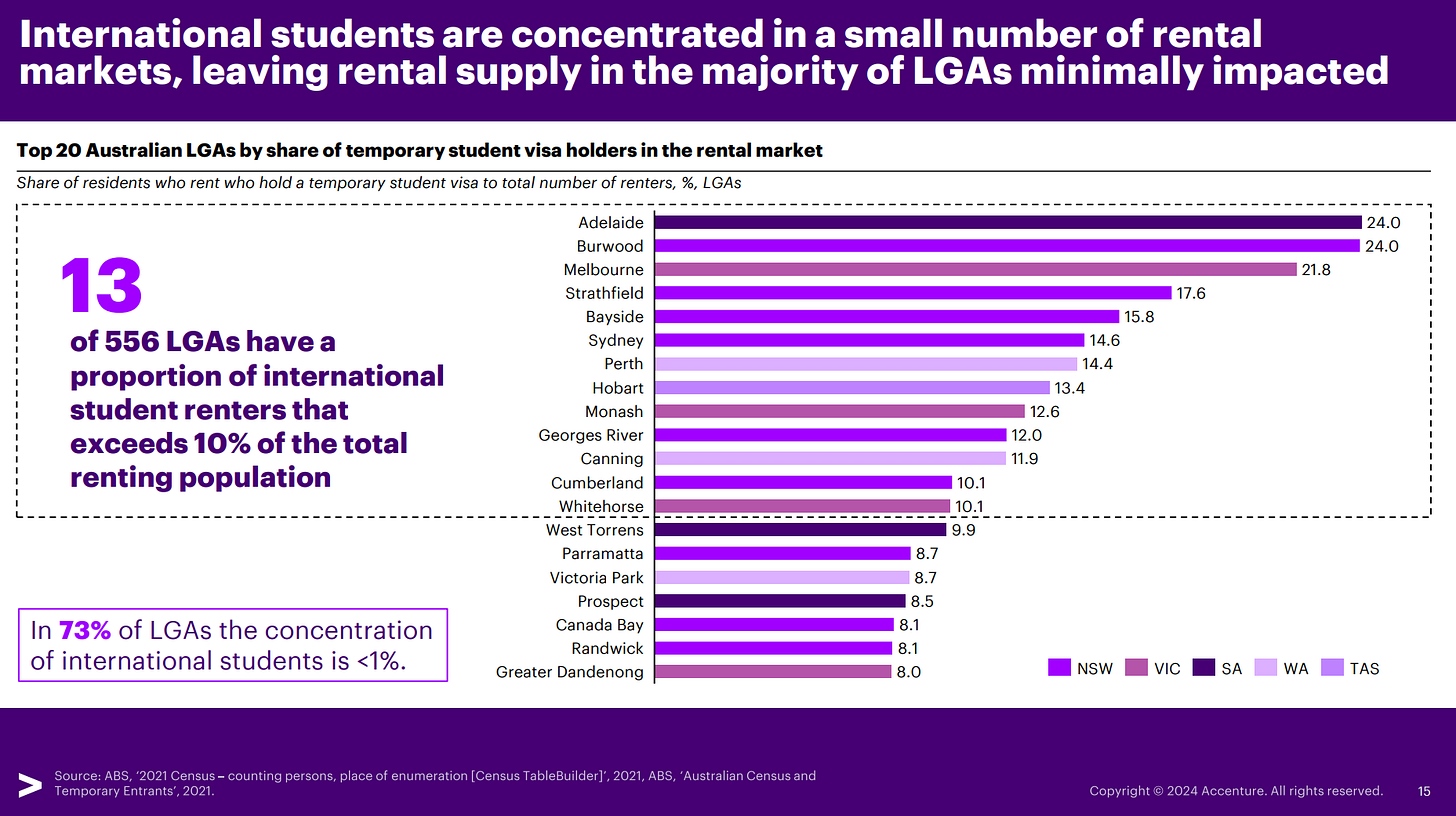

Lets borrow this slide, after they’ve noted that the stock of international students are 4% of renters in Aussie:

So in these regions with high exposure to international students, additional demand for housing will push up rents and prices for those who own the property, and thereby crowd out other people who may have been willing to live there. The size of this effect depends on the elasticity of supply - and since Australian neighbourhoods and voting public is loaded up with people who don’t want to live near other people, NIMBY policies are in place that limit any supply response.

A tricky thing is asking about the substitutability of housing. When I was a student I lived with 6 other people in an derilict abandoned office - it was directly behind a bar, was infested with mice, and there was constant violence outside. A perfect environment for learning economics, but not really a location that would be used for raising a family.

However, if we did not exist there may have been a gradual process of the housing stock being changed towards a higher quality that families could use. That building is currently abandoned, so in that case it is unlikely, but that is another margin - the stock would evolve through time, meaning that without perfect substitutability there will be a gradual effect.

PropTrack took the next step in chatting about this, noting that rent growth has been high in certain areas that are more heavily exposed to international students. However, they also note that this is very localised and so the overall effect on the housing market - even with building constraints - will be very small. The key factor for average affordability really is building more.

It is for this reason there has been a government commitment to set the cap relative to the housing supply provided by universities - a concept that is interesting, but given there are no available details (even about the institution level caps sensitivity to this building) it is a bit hard to evaluate.

Furthermore, we can see there there is a pretty loose relationship between this and where the caps are biting in the first place …

Some spillovers are good too

But lets not forget the other scale advantages. Increasing the size and reach of the university allows the university to hire more experienced researchers and teachers - boosting both the accumulation of knowledge in Australian and the quality of teaching to Australian students.

Having foreign students come to the country helps to build networks between Australia and other countries - supporting export activities by building relationships, and increasing the chance that these newly trained individuals will want to come and create and produce within Australia.

These channels aren’t abstract. As a New Zealander I’d always heard a lot about migration and trade - but recent research expands this to look at the role of international students, finding significant effects on trade which are especially important in countries that are relatively “dissimilar”.

This has been recognised in Australia, with the 2023 review into tourism and export education highlighting making better use of alumni networks as a key target for future development of the industry.

The teacher quality point is something I’m less familar with. I will be blunt though, the large Australian Universities have hired top quality staff and have a reputation for modern and engaging teaching - this comes from funding and scale. If you think we can slash student numbers without sacrificing some of this you are dreaming.

How does it all net out

See this is a question the government should aim to answer before establishing large restrictions on the ability for an industry to export - but it is hard to say much as it doesn’t appear much genuine thought has gone into it.

The burden of proof isn’t on a random blogger to establish that export bans might not be the killer policy to meet every government objective - it is on the person imposing the ban to do due diligence.

All I can say is, given what we looked at above, the policy won’t do much of anything related to house prices but will have real costs for Australian students, knowledge creation in Australia, and benefit from trade for Australia.